Only a small percentage of people who lived during the American Colonial period had portraits painted of themselves, and they were generally members of the higher levels of society. For the rest, we rely on contemporary descriptions regarding a person’s appearance, but In many cases, those are woefully inadequate. Often they merely state that a person was above or below average height, with a powerful or slight physique, having light or dark hair, and an attractive appearance. Often those few characteristics are contradictory, depending on who is describing the person.

When we write about people of the 18th century, a visualization of a person gives us a bit more of a personal connection with them. So, we endeavor to find whatever extant likenesses that are available, or draw our own image of them that is based on whatever contemporary descriptions we can find. In that way, we have a visualization of sorts that gives us a somewhat personal connection while we are writing about them. Of course we don’t have to do that in those instances when we’re writing notable historical figures like George Washington, Paul Revere, or someone who has been painted by the likes of John Singleton Copley or other 18th century artists. However, well known characters of American history like Nathan Hale, Sally Townsend, Christopher Gist, or Hercules Mulligan apparently did not have their portraits painted, or at least, we have not been able to locate them. In those cases, we’ve used whatever contemporary descriptions we could find to generate a picture of what we believe they may have looked like.

Those pictures pictures of personalities are shown in this section along with a description of the basis of our drawings.

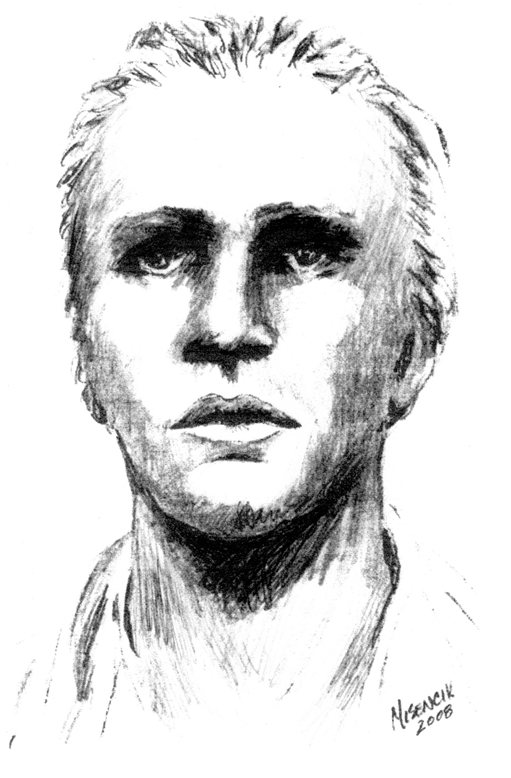

Captain Nathan Hale (1755-1776) – The First Spy

Captain Nathan Hale was General Washington’s first spy, and his mission ended in disaster, but the lessons learned from his ill-fated mission benefitted future espionage missions. While there are no surviving contemporary images of Nathan Hale, our drawing is based on descriptions of him that were made by acquaintances and admirers, and we’ve also relied on the statue of Nathan Hale at Yale University. In his early years, Nathan was a sickly child, but through vigorous excerise he grew into a strong, healthy and very intelligent young man. He was described as strikingly handsome, with a slender build, fair skin, a ruddy complexion, light hair, clear, light blue eyes, and a soft “musical” voice. He was taller than the average height, standing just under six feet tall. He had what was described as a cheerful and generous manner, naturally at ease with social graces, and was mature beyond his years. He was popular in his community and one acquaintance, Dr. Aeneas Munson described Nathan Hale as “a diamond of the first water, calculated to excel in any station he assumes. He is a gentleman and a scholar, and last, though not the least of his qualifications, a Christian.”

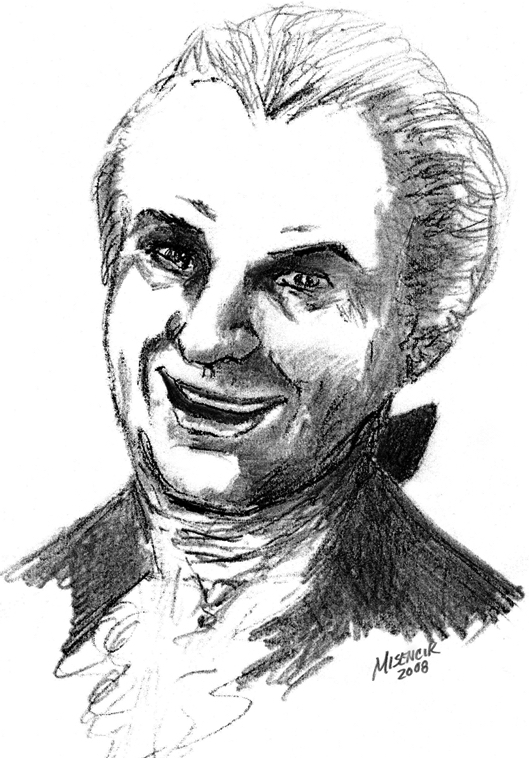

Doctor Benjamin Church (1734-c.1780). The Sons of Liberty Spy

Benjamin Church was a native of Boston, and a descendant of a long line of honest and respected ancestors. His father was Benjamin Church, a well-known merchant and church deacon who served under the Rev. Mather Byles of the Hollis Street Congregational church. His grandfather, the famous Colonel Benjamin Church achieved fame during “King Philip’s War” (1675-76), when the Wampanoag and Narragansett Indians attempted to exterminate the white colonists in Massachusetts. Young Benjamin was educated at the Boston Latin School, and graduated from Harvard College in 1754, where he received his medical education under the renowned Dr. Joseph Pynchon at Harvard, and next studied surgery at London Medical College. In addition to his medical practice, Dr. Church was a writer whose published works of poetry and prose were well received by the Boston public. He was witty, urbane, and was a favorite among Boston’s rich, and powerful. He also became very closely associated with Boston’s patriot faction and was closely associated with the likes of Paul Revere, Samuel Adams, John Hancock, John Adams, and Dr. Joseph Warren, all of whom were leaders of the rebellious group the Sons of Liberty. Through his association with the patriot leaders, Dr. Church was invited to become a member of the Sons of Liberty, and in a short time became one of the secret organization’s leaders. In fact, he became a member of “The Mechanics,” the most secret unit within the organization. But Doctor Church was something else altogether; he was a mercenary spy who supplied British Royal Governor Thomas Gage with the innermost secrets of the patriotic movement. Indeed, It was Gage, whose information led to the British march to Lexington and Concord in mid-April 1775, which began the Revolutionary War. Our drawing of Dr. Church is based on a posthumous painting of Dr. Church at the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

John Honeyman (1729-1822) The Christmas Spy

John Honeyman was a veteran of the French and Indian War, and was with General Wolfe’s army at the climactic battle for Québec in 1759. In fact, it’s said that Honeyman carried the mortally wounded Wolfe from the battlefield. During the darkest days of the American Revolution in 1776, while Washington was driven out of New York and across New Jersey, Honeyman approached Washington and volunteered to spy for him. Acting as a British sympathizer, he plied his trade as and itinerant butcher and purveyor of beef. In that role, he was able to visit most of the British and Hessian camps in New Jersey, and was generally well received as a former British soldier. While he was accepted by the British and Hessians, he was reviled as a traitor by his fellow Americans, who threatened his family and sought to capture his as a spy. Allowing himself to be captured in late December 1776, Honeyman was personally interrogated by General Washington in private, during which time he gave the general information, which led to the victory that saved the American Revolution. Honeyman was scheduled to be tried and likely executed as a spy, but during the night, he escaped under very suspicious circumstances. After the war, Washington personally vouched for Honeyman’s patriotism and his contributions to the final victory. There are no surviving illustrations or extant descriptions of John Honeyman. Our sketch of him is how we envisioned him when we wrote about him.

Lydia Barrington Darragh (1728-1789) The Quakeress Spy

Lydia Barrington Darragh, and her family were Quakers, whose faith was committed to unwavering pacifism. However, a strange set of circumstances caused her to spy for General Washington. Lydia’s timely information to Washington regarding a massive British attack on the American forces prevented a catastrophic British victory. There are no surviving contemporary images or descriptions of Lydia Barrington Darragh. Our drawing allowed us to visualized they way we envisioned her as we wrote the story of her clandestine adventures.

Ann Bates (1748-?) The Most Effective Spy

Ann Bates of Philadelphia was described as attractive, charming, and very intelligent, and she was perhaps the most intrepid, and successful spy during the Revolutionary War, if not of all time. Unfortunately for the Americans, Ann spied for the British. She was a schoolteacher, kept bees, and ran a small store. Even though she married a British artillery soldier during the British occupation of Philadelphia, Ann was so pleasantly congenial that she was exceedingly popular with both the Philadelphia Patriot and Loyalist communities. After the British evacuated Philadelphia for New York City, Ann took the merchandise from her store and traveled to the far-flung American army camps as an itinerant peddler. In that way, she was able to gather valuable intelligence regarding Washington’s army for the British high command in New York. Her adventures are almost beyond belief, and she was so brazenly skillful that she penetrated George Washington’s very headquarters. In addition, she sweet-talked two American generals out of safe conduct passes to visit American camps., On at least one occasion, she traveled in the company of General Charles Scott, Washington’s chief of intelligence, often dining with him in his headquarters tent. Many spies were undone by the notes and other information they secreted upon their person, but Ann’s eidetic memory gave her the ability to store and accurately recall prodigious amounts of data in her mind. This was often confirmed when compared to information furnished by other British spies. Ann can rightfully considered to be a Revolutionary War era “James Bond.” There are no extant likenesses of Ann Bates, and our sketch is pure conjecture.

Hercules Mulligan (1740-1825) The Affable Spy

The Irishman Hercules Mulligan was a natural-born raconteur who had the melodic lilting brogue of an Irish bard. In addition, his congeniality, out-going personality, quick wit, and natural gift of gab endeared him to Manhattan’s citizenry regardless of their political persuasion. Mulligan’s personality traits served him well as the most fashionable tailor and clothier in all of the English colonies. His shop at 23 Queen Street on Manhattan under the sign of the Golden Thimble and Shears that advertised “H. Mulligan, Clothier was visited by the highest levels of New York society and high-ranking British officers. Mulligan kept a plentiful supply of spirits on hand as well as tasty treats for his clientele, and often his visitors stopped by merely to chat with Mulligan while he generously refilled their glasses with the finest wines. He was indeed a very successful New York businessman, but he was also an American spy. Interestingly, Mulligan was everything a spy should not be. He had a flamboyant name to go with his flamboyant personality, and he was not at all coy about his preference for the American patriotic faction. Even though most of the top echelons of the Loyalist citizenry were aware of his patriot sympathies, they still continued to do business with Mulligan or just as often, stopped by for a drink and a chat. With the aid of his servant Cato, Mulligan smuggled military intelligence out of the city to Washington’s headquarters. Once again, there are no surviving images of Hercules Mulligan that were made during his lifetime.

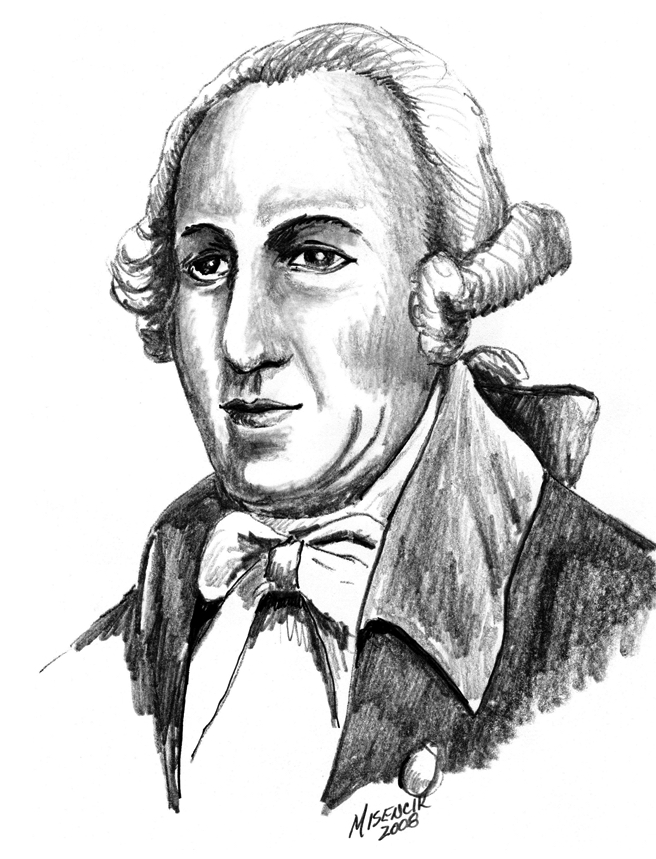

James Rivington (1724-1802) The Conflicted Spy

To paraphrase Winston Churchill, James “Jemmy” Rivington, is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma. He was the most successful publisher in the American colonies whose newspaper circulation was greater than many of the largest European papers. He was so outspokenly pro-British in print and speech that he was universally reviled by American patriots. From being a well-respected newspaper that offered differing options and viewpoints, Rivington’s Royal Gazette became a pure British propaganda rag, filled with pro-British lies and misstatements. At one time, American patriots rode into New York and destroyed Rivington’s presses and carted off the lead type to be molded into musket balls. Rivington fled to England, only to return with new presses, and a commission as the “Printer for the King.” At the same time, Rivington opened and operated a coffeehouse in partnership with Robert Townsend, one of the two leaders of the Patriot spy network, the “Culper Ring.” Their business was frequented by British, Hessian, and Loyalist officers, and proved to be a gold mine for military information that was forwarded to General Washington. Even so, historians are unsure of Rivington’s true allegiance, and it seems that the printer himself was conflicted about which faction to support. Washington, himself saved Rivington from harm and exile after the war, but Rivington refused to divulge his true sympathies, even though it cost him dearly. Our drawing of Rivington is based on a painting by Gilbert Stuart.